28.02.2025

Dirty And Unregulated Industrial Salmon Farms

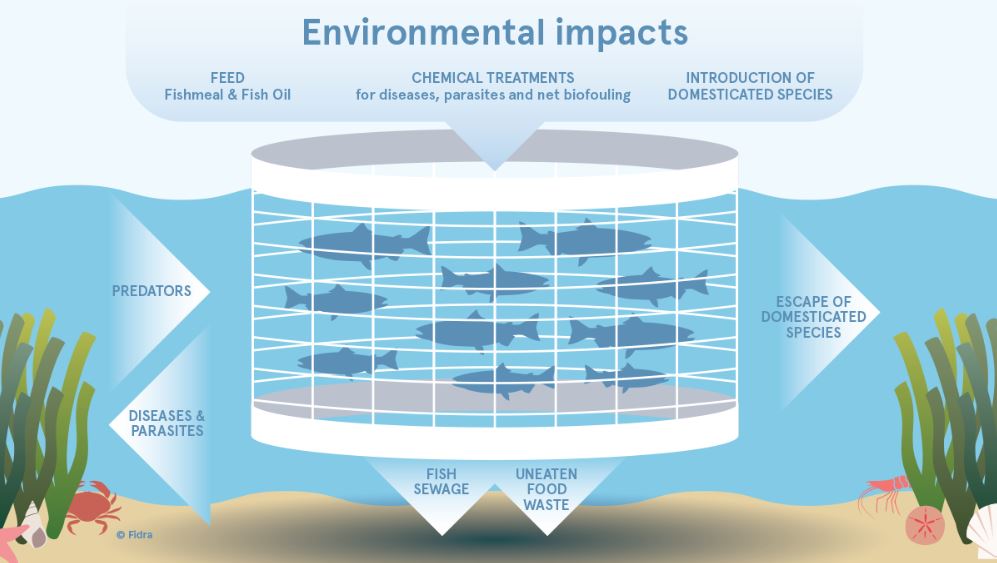

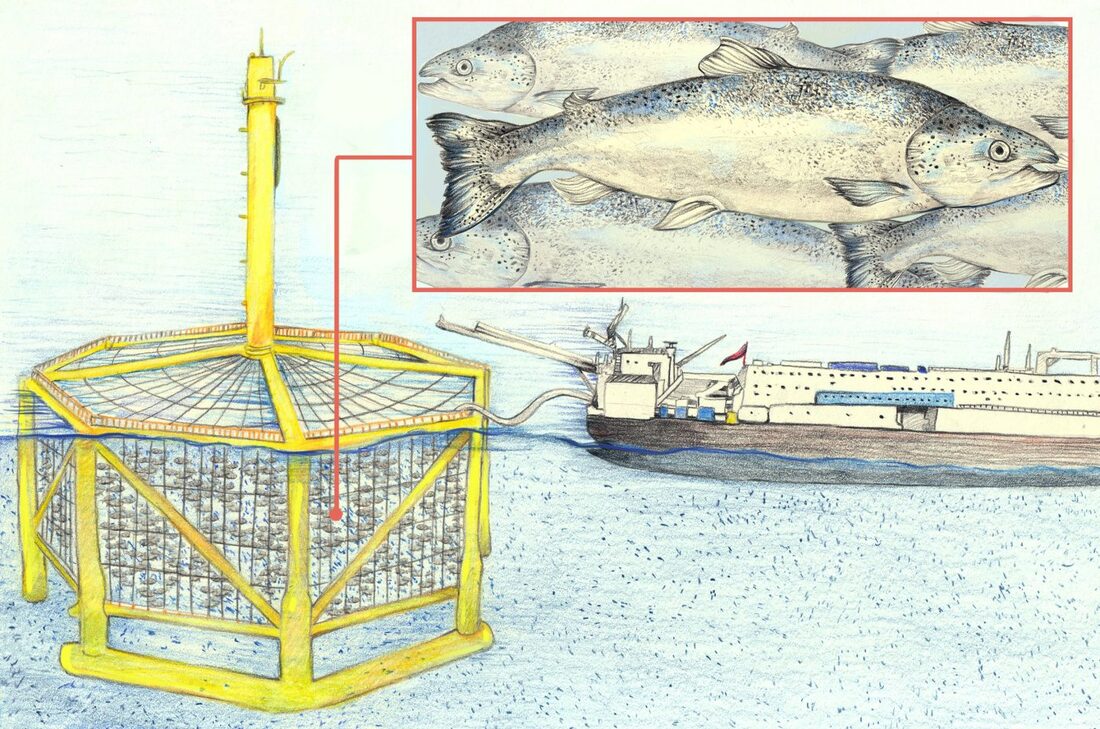

Over the past 30 years, industrially farming salmon in the ocean has become a massive industry. These farms now dot coastlines around the world with their rows of net-covered salmon pens, including in Maine, New Brunswick, British Columbia, Norway, and Iceland. A “net pen” is like an iceberg: not much is visible from the surface. But beneath the waves, up to hundreds of thousands of fish crowd each floating pen. The fish eat and grow at astounding rates – and defecate. A typical industrial farm of several hundred thousand fish produces around one million pounds of waste annually. That’s roughly the same amount of sewage generated by Maine’s largest city, Portland, in a year. The poop is not captured or treated. Instead, it floats out through the pens to pile up on the ocean floor. The waste accumulates over time to form a layer of foul-smelling black sludge that is toxic to small bottom-dwelling creatures. Eventually, the seafloor around an industrial salmon farm will transform into a lifeless landscape. Fish also produce a lot of nitrogen waste. Nitrogen pollution mixed with warm water creates perfect conditions for toxic algae outbreaks. The algae can grow out of control to form massive red tides that poison any fish, turtles, and shellfish in their path. Nitrogen pollution also clouds the water, blocking eelgrass nurseries on the seafloor from essential sunlight. Small crustaceans, known as sea lice, cling to salmon and eat their skin. In natural conditions, sea lice parasites attach in small numbers, making them a minor issue that doesn’t affect a fish’s health. But in industrial salmon farms, they spread easily between captive fish, covering affected fish with open sores. A severe sea lice infestation can kill entire generations of farmed fish. To control sea lice, the salmon industry has historically used chemical treatments and pesticides – including some that kill crustaceans like lobsters.

Credit: Brut.

Credit: Brut.

Poverty deprives people of adequate education, health care and of life's most basic necessities- safe living conditions (including clean air and clean drinking water) and an adequate food supply. The developed (industrialized) countries today account for roughly 20 percent of the world's population but control about 80 percent of the world's wealth.

Poverty and pollution seem to operate in a vicious cycle that, so far, has been hard to break. Even in the developed nations, the gap between the rich and the poor is evident in their respective social and environmental conditions.

Poverty and pollution seem to operate in a vicious cycle that, so far, has been hard to break. Even in the developed nations, the gap between the rich and the poor is evident in their respective social and environmental conditions.